By cuterose

How to make sense of your fitness app’s privacy policy

One of the ways that connected fitness apps keep you exercising is by using accountability — the ability to share your workouts with friends so you can urge each other onward — but wanting to share with your pals is different than wanting to share with an app developer or some anonymous marketer.

How much of your data is shared, and to whom, is usually set out in the privacy policy that most people accept (and don’t bother to read) when they are installing an app. To see exactly what you are agreeing to, we took a look at the privacy policies of some popular fitness apps. Some are good. Some are alarming. For many of them, there may be things that you will want to manually opt out of if you want to guard your privacy.

But before we begin, let’s start with a general observation: if you link your fitness account with your Google or Facebook account for login purposes, you’re giving the company access to your contact list and social activity. You may not want to do that.

Second, most apps will want to use the ad-tracking features native to your platform. You can turn them off:

Finally, note that the directions in this article are for US users. If you’re in Europe, GDPR may apply, and the rules are more in your favor.

Strava

With Strava, you own all of the content you create: workouts, data, photographs, posts, and so on. (If you create a route and make it public, that belongs to Strava.) However, the company claims the right to use that content and your name — including in ads pushed to other users — unless and until you delete it. If you upload your contacts or link your account with other social media accounts, it uses that to suggest other people you may want to follow. This all sounds obvious, but do keep this in mind: the more information you give it, the more information it has.

By default, you give Strava access to everything you do on its platform, and your profile and activities are public. Strava, for instance, maps your runs, which can be useful. But that feature can expose exactly where you live, work, or exercise regularly. You can mask that, but you should be aware that you’ll have to do it manually through the app settings.

How to opt out: Fortunately, Strava gives you a great deal of control over how exposed your data is. Besides its formal privacy policy, which is written in reasonably comprehensible English, Strava has published a blog post that clearly walks you through ways to protect your personal data.

Fitbit

Fitbit doesn’t collect as much data as Strava does, but its platform isn’t as ambitious, either. It does collect the data that you presumably want it to gather — steps, heart rate, weight, sleep stages — and tracks your location, step data, and coached classes.

But remember that those coaching services may be provided by a third party, like one of Fitbit’s services or possibly your employer or insurance company. If you take a class, Fitbit collects information about your plan, your goal, your communications with your coach, and even the notes that your coach keeps about you. (That last bit may be especially creepy if the class is provided or required by your employer or insurance company.) In addition, the company may use your information to feed you customized insights.

How to opt out: You can decline to share most personal information, and you can control many social notifications. Open the app, go to the Account screen by tapping the icon on the app’s upper left corner, and proceed to the “Privacy and Security” section.

Fitbit says it may aggregate and de-identify your data and disclose it publicly in reports or to marketing partners. You cannot opt out of that.

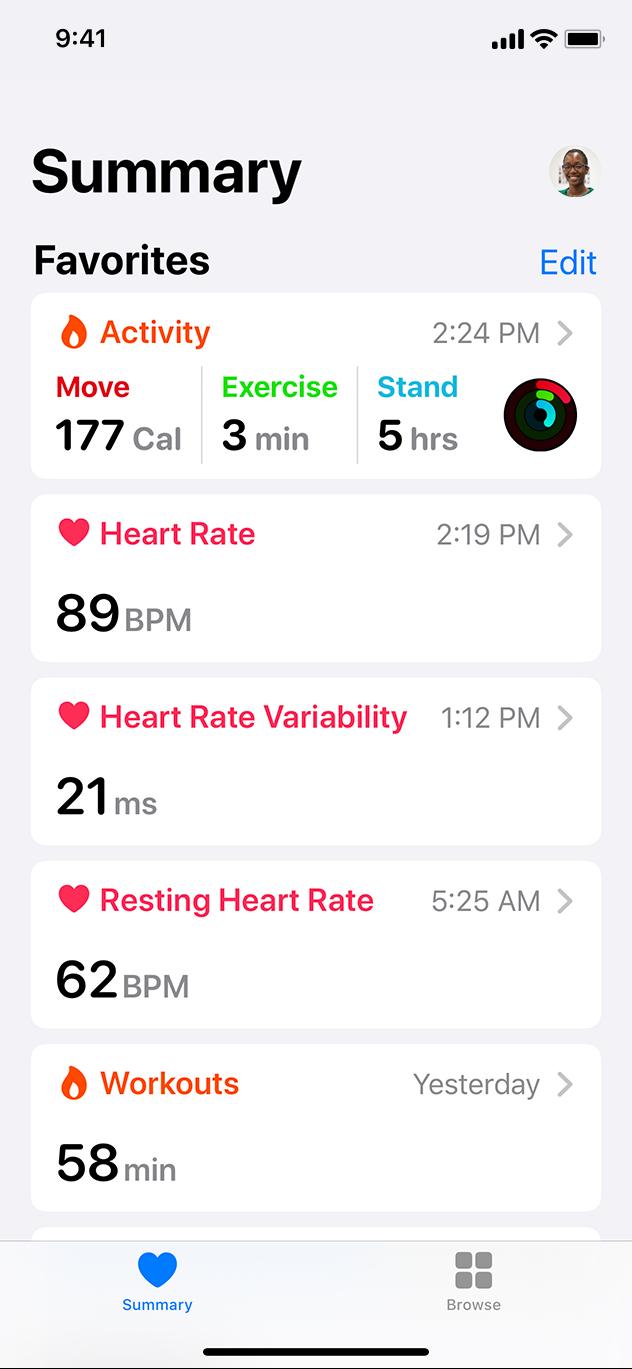

Apple Health

Your iPhone and Apple Watch probably know everything about you. Apple says your personal data is encrypted; the company can’t see it, and it doesn’t market it to third parties.

How to opt out: As with Apple’s other products, you can opt out of Apple’s marketing mailing list by going to your Apple ID preferences, and you can limit ad tracking.

Couch to 5K

Zen Labs’ privacy policy is a little slippery. First of all, it’s available only on your phone; the policy on the web is only the policy for its partners. Digging through the app (by going to Settings > Consent Management), you learn that C25K collects and shares your device’s advertising ID and location data so companies can push ads to you. (Zen Labs says no personally identifiable data is included.) Tracking is on when the app is running in the background, too.

One of Zen Labs’ partners, Sense360, also collects a list of the other apps on your phone, including when the apps are closed. Sense360’s site indicates that it serves mostly the fast-food industry, which makes it kind of an odd partner for C25K.

How to opt out: Other than turning off your ad tracking, there’s no way to opt out of C25K’s tracking.

MyFitnessPal

MyFitnessPal is part of Under Armour, which has lots of different parts, so its privacy policy is extensive and dense. Some of the data you provide by using the app gets used to feed you targeted workouts and other fitness-related content.

Basically, the MFP policy says that whatever you do or connect to on its app, it can share with third parties. That includes making associations between your MFP account and other users, other social media accounts, or anyone else. That information is not necessarily anonymized.

Apple users catch a break: Under Armour says its partners treat iOS data according to Apple’s Developer Guidelines, which are strict about privacy. Android users are apparently on their own.

How to opt out: You can control what you publicize to other users about your activity and control how much email the app sends you about your friends’ achievements. You can also turn off MFP’s ability to feed you location-based ads by going to the lower right corner of the app and selecting More > Privacy Center > Personalization. There is no apparent way to opt out of MFP’s third-party sharing other than to turn off ad tracking entirely.

Vox Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. For more information, seeour ethics policy.